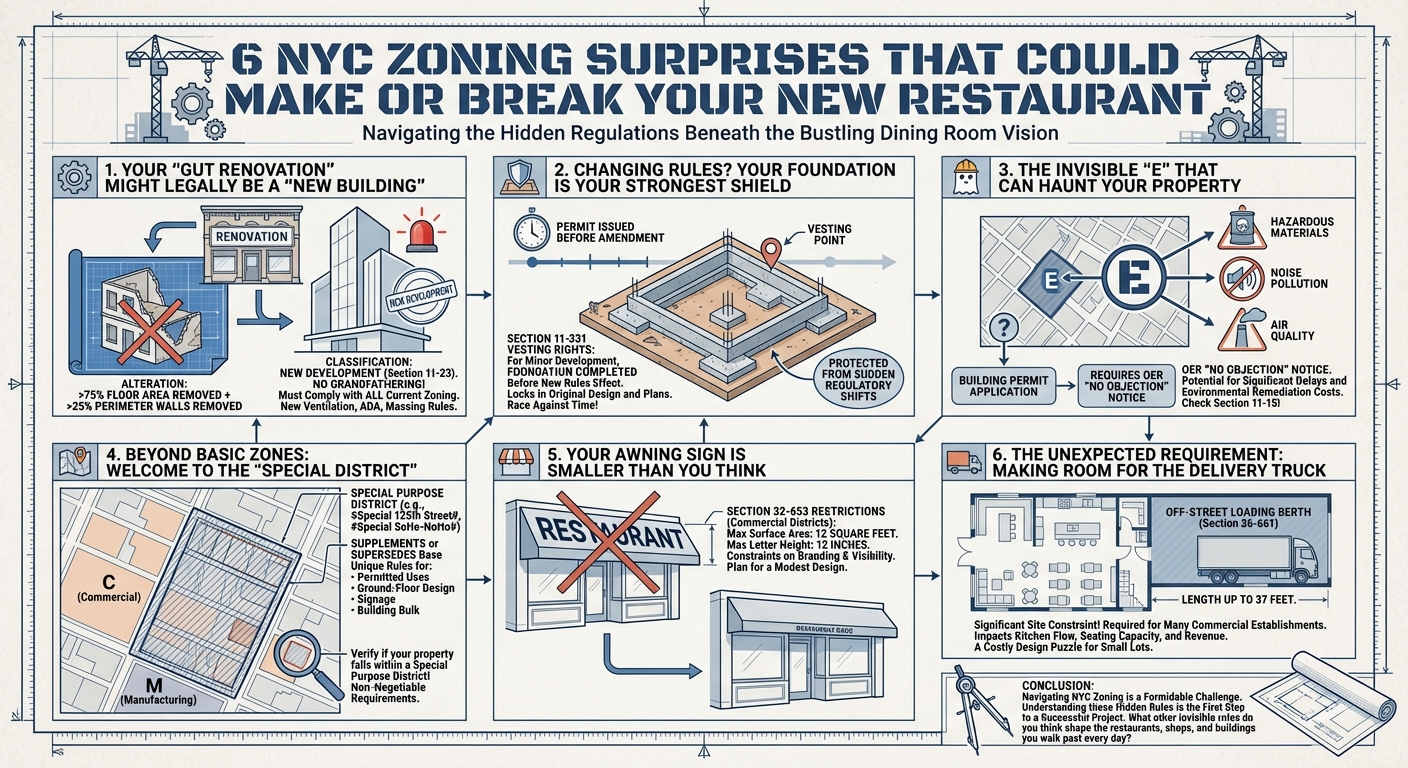

6 NYC Zoning Surprises That Could Make or Break Your New Restaurant

Opening a restaurant in New York City is a classic dream. But beneath the vision of a bustling dining room lies a complex, often unseen web of zoning regulations that governs every beam, window, and square foot of space. Aspiring restaurateurs often focus on menus and marketing, only to be blindsided by rules that can dictate the fundamental feasibility of their project. This guide illuminates some of the most surprising and impactful regulations, drawn directly from the city's official Zoning Resolution, that every future NYC restaurateur needs to understand.

1. Your "Gut Renovation" Might Legally Be a "New Building"

It's a common assumption that no matter how extensive a renovation is, it remains an alteration of an existing building, grandfathered under older, often more lenient rules. However, the NYC Zoning Resolution has a counter-intuitive rule that can dramatically change the legal status of a project.

According to Section 11-23 ("Demolition and Replacement"), the alteration of an existing building is legally considered a new "development" if it involves the removal of more than 75 percent of the floor area and more than 25 percent of the perimeter walls.

This reclassification is critical for any restaurateur. Being considered a new "development" means the project is no longer grandfathered and must comply with all current zoning regulations. This could trigger entirely new and far more restrictive requirements for building use, massing, parking, and facade articulation. For a restaurant, this could suddenly mandate a different type of ventilation system required for new builds, or trigger modern ADA compliance rules that didn't apply to the old structure, directly impacting the programmatic needs of kitchen and bathroom layouts. What began as a renovation can suddenly face the site constraints and costs of an as-of-right new build.

2. Changing Rules? Your Foundation Is Your Strongest Shield

Imagine you have secured permits, broken ground, and started construction on your dream restaurant, only to learn that the city has amended the zoning regulations for your neighborhood. This scenario can be a developer's nightmare, but the Zoning Resolution provides a powerful, if time-sensitive, protection.

The concept of "vesting rights" is outlined in Section 11-331 ("Right to construct if foundations completed"). It states that if a building permit was lawfully issued before a zoning amendment took effect, construction may continue under the old rules, but with one crucial condition. The rule distinguishes between project sizes: for a minor development, "all work on foundations had been completed" prior to the new amendment's effective date, while for a major development, "the foundations for at least one #building# had been completed."

For a single restaurant project, likely a minor development, completing the foundation acts as a legal vesting point, locking in your project's original design and approved plans. This single rule highlights the high-stakes race against time that can define development in New York City, where finishing the foundation can be the one thing that protects a project's budget and vision from being upended by sudden regulatory shifts.

3. The Invisible "E" That Can Haunt Your Property

An aspiring restaurateur might find a seemingly perfect location—great foot traffic, ideal size, and the right price—unaware of hidden environmental restrictions that can bring a project to a halt before it even begins.

This hidden threat is the "(E) designation," a note in the city's records governed by Section 11-15 ("Environmental Requirements"). This designation indicates that a specific tax lot has environmental requirements related to potential hazardous materials, noise pollution, or air quality issues.

The consequences are significant. Before the Department of Buildings (DOB) can issue a building permit for a new development, enlargement, or even certain changes of use, the property owner must first obtain a notice from the Office of Environmental Remediation (OER) stating that OER has no objection. This is a crucial and often overlooked step in the due diligence process. Discovering an unexpected (E) designation can lead to substantial delays and unforeseen costs for environmental testing, remediation, and mitigation before any construction can commence.

4. Beyond Basic Zones: Welcome to the "Special District"

Most people are familiar with the basic zoning categories, such as Commercial (C) or Manufacturing (M) districts. However, New York City's zoning has another, more granular layer of regulation that can impose highly specific rules: the Special Purpose District.

These districts, such as the "#Special 125th Street District#," "#Special SoHo-NoHo Mixed Use District#," or the "#Special Sheepshead Bay District#," overlay the base zoning. Their purpose is to establish unique, hyper-local rules that either supplement or supersede the standard regulations of the underlying zone. These special rules can govern nearly any aspect of a building's design and function, including permitted uses, ground-floor design, signage regulations, or building bulk.

For a business owner, the takeaway is clear: it’s not enough to know your property’s base zoning. You must also verify whether it falls within a Special Purpose District. These overlays can introduce unexpected and non-negotiable requirements that will fundamentally shape your restaurant's design, facade articulation, and operation.

5. Your Awning Sign is Smaller Than You Think

A restaurateur might envision a large, prominent sign on their awning to capture the attention of passersby, a key part of their branding and street presence. However, the Zoning Resolution places strict and often surprising limits on this common feature.

According to Section 32-653 ("Additional regulations for projecting signs"), in many commercial districts, non-illuminated signs displayed on awnings or canopies are severely restricted. The rules limit the sign's surface area to a maximum of 12 square feet, with the height of any letters not exceeding 12 inches.

This tiny detail can fundamentally alter a restaurant's exterior design and marketing strategy. A plan for a bold, distinctive awning sign must yield to a much more modest design. This constraint on facade articulation forces owners to rethink their entire approach to branding and visibility, highlighting how even the smallest zoning rule can have a significant impact on a business's public identity.

6. The Unexpected Requirement: Making Room for the Delivery Truck

When planning a restaurant's layout, the focus is naturally on optimizing the programmatic needs of the kitchen and dining room. A crucial back-of-house requirement, however, is often overlooked until it becomes a major design problem: the off-street loading berth.

Article III, Chapter 6 ("ACCESSORY OFF-STREET PARKING AND LOADING REGULATIONS") stipulates that many commercial establishments must provide dedicated, off-street space for deliveries. The scale of this requirement can be surprising. As specified in Section 36-661 ("Size of required berths"), a standard required loading berth can be up to 37 feet long.

For a restaurant project on a small or narrow lot, this isn't just about losing space; it's about redesigning the entire flow of your back-of-house, potentially forcing a smaller, less efficient kitchen or sacrificing seating, which directly impacts revenue. Dedicating this much space—the length of a large truck—is a significant site constraint and a substantial cost, turning what should be a pragmatic logistical requirement into an unexpected and costly design puzzle.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Navigating New York City's Zoning Resolution is a formidable challenge, but understanding its surprising and often hidden rules is the first step toward a successful project. These regulations are not just bureaucratic hurdles; they are the invisible blueprint that dictates the city's massing, use, and street-level experience. Now that you've seen the hidden complexities, what other invisible rules do you think shape the restaurants, shops, and buildings you walk past every day?